Perhaps the most pressing issue for the Australian Navy by the end of October 1914 was the transport of the troops to engage in the conflict under-way across Europe and the middle East.

However worries about the continued presence German naval vessels in the Pacific and the organisation of both troopships and a guard for the convoy delayed their departure.The contingent of troops had been organised at high speed during August 1914.

Its equipment had to be manufactured or purchased equally quickly as it was expected the troops would be depart almost immediately. To ensure this happened troop vessels were transformed from merchantmen into transports and assembled at the ports of departure around Australia and New Zealand.As the inevitable delays mounted up military authorities suggested sending off the slower vessels, conveying horses sometime around the 26August and allow the quicker infantry transports to catch them up en-route.But the Admiralty refused to let any transports leave without escorts because it had no up-to-date information on the location of any German warships which may be plying the waters of the Indian Ocean. This meant he escort would not be available until the Psych and Phillowl returned to New Zealand from Samoa and the Sydney and Melbourne made it back from New Guinea.

There were proposals to send the New Zealand troops from Wellington on the 20th of September, under escort of the small cruisers, and join the Australians off Adelaide, the combined forces could then be escorted by the Sydney and Melbourne via Fremantle, Colombo, Aden, Suez to Europe.On the 8th of September, Admiral Jerram was informed that by the end of the month the Minotaur and Hampshire must be sent to the Cocos Islands to guard the contingents as far as Colombo. Two days later Admiral Paley was informed that the Australia must accompany the convoy; the Minotaur was for the time being held back.

On the 13 September The New Zealand Government announced their transports would leave on the 25th, but suggested that they should be taken direct to Fremantle by the three small cruisers Plzilomel, Psyche, and Pyratnzrs. The next day the Australian Government promised its twenty-seven transports would be assembled in King George’s Sound by the 5 October.In a strange twist of fate the big German cruisers appeared at exactly the same time. They appeared off Apia, in Samoa, on the 14th of and left it steering north-west, and it was at this time also that the Emden’s exploits in the Bay of Bengal came to light.The effect on the New Zealand Government was immediate. Governor of New Zealand “expressed considerable uneasiness ” about sending off its troopships. Of the prospective escort, the Hampshire had been ordered off to find the Emden; the Australia and Sydney were held in the Pacific to stand guard over the Rabaul expedition; and only the Melbourne was on its way south to cover the Australian transports.

It is true that, instead of the Australian Squadron, the Admiralty ordered the Minotaur with the powerful Japanese cruiser Ibuki to meet the convoy at Fremantle on the 4th of October. This might ensure safe voyage across the Indian Ocean; but, with the Germans at large in the waters around Australia and New Zealand the risk now seemed much more serious. Fremantle, while convenient as a point of departure, was quite inadequate as an assembly area whereas King George’s Sound filled all requirements. Unfortunately the telegrams from the British Admiralty continued to refer (by mistake) to Fremantle as the place of assembly.

As a result New Zealand was faced with an unenviable decision. With no strong naval force available, should it wait for the Second Convoy to Europe six weeks while the first Australian contingent had left or should it sail with its tiny escort into waters in which armoured German cruisers were at large. Surprisingly given their Governors unease they decided to send their transports immediately.

Two left Auckland on the 24 September, escorted Ily the Philoillel, the others were to sail nest day, when the the situation suddenly changed with the arrival of a telegram from the Governor-General of Australia. This telegram conveyed tot his New Zealand inequivalent his private opinion that the New Zealand transports ran a grave risk, and should not sail until the Admiralty had been consulted.1 This unusual step which by-passed the Australian Government lay in the growing uneasiness felt by the newly elected Australian Ministry at the possibility however remote, of the enemy sinking unescorted transports and thereby inflicting not only tragic loss, but such a shock as might destroy Australian faith in the Admiralty.

The new Australian Government led by Andrew Fisher, had taken office only three days after the German cruisers3 had left Samoa, and as a result were anxious about the convoy of transports. Fisher had conjured up a picture of thirty thousand young untried men afloat, of enemy cruisers dashing in to sink them, of Australia, unused to war, shocked and angered. At so early a stage, he felt, the sinking of a transport,from preventable causes, might push Australia practically out of the war for many months. With these views his Ministers and the Governor-General, Sir Ronald Craufurd Munro Ferguson4, entirely agreed. In Sir Ronald’s opinion, the destruction of these transports especially of the whole thirty-eight after their assembly in Australian waters, would be the most significant blow Germany could effect in the Pacific.5

The telegram’s effect was immediate. The Plziloiirel and her two transports were recalled and they telegraphed the Admiralty: Departure of New Zealand expedition had been delayed on account of telegram received by Governor of New Zealand from Governor-General of Australia who considers Tasman Sea may not be safe.

The Admiralty’s reply was to offer the Minotaur and Ibuki visit Wellington to escort the troopships and pick up Australian transports on way. In addition however it suggested that the troopships at sea be brought to Melbourne and departure of others delayed pending their further instructions.

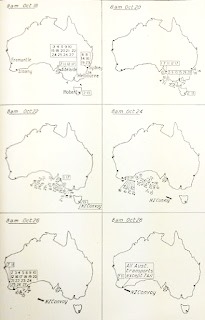

By the end of the September 1914 every transport was in harbour waiting for orders to proceed. At the same time the Admiralty hurried forward the Minotaur and Ibuki which reached Fremantle on the 29 September and Hobart nine days later. However nothing could be done until the New Zealanders arrived. Finally on 16 October at 7 a.m. the Minotaur, Ibuki, Pliiloiitrl, and Psyche, with ten transports in charge, left Wellington for Albany, touching at Hobart on the way. The Naval Board at once issued orders that all Australian transports must reach Albany by the 28th and they proceeded independently, although the Melbourne continued to cruise off Gabo Island until the last transport from Sydney had safely passed that point.By 28 October the whole Australian convoy of 26 vessels ranging from the 1g.ooo-ton Eltripides to the 5,m ton horse-transports were assembled alongside the New Zealanders, who had made the utmost possible speed, in spite of heavy weather.The Minotaur took charge of the whole convoy which at last left Australia on 1 November 1914.

6.25 am Minotaur and Sydney sailed

6.45 am First Australian Divisions sailed

7.15 am Second Australian Division sailed

7.55 am Third Australian Division sailed

8.20 am New Zealand Division sailed

8.53 am All transports clear of Sound

8.55 am Melbourne weighed anchor and proceeded

The Ibuki had gone ahead to Fremantle to pick up two transports the Medic and Ascanius and joined the convoy on 3 November.Positions of the troopships and escort of the First Convoy to leave Australia, 1914, A Jose, The Royal Australian Navy 1914 -1918, 1933Five miles ahead of the rest moved the Minotaur. Behind came the transports commanded in the main by merchant seamen unused to formation sailing. This meant it took some time for them to get used to the slow speeds and regular station keeping. In addition they had problems at first suppressing lights at night except oil side-lights and a shaded stern-light. However one eyewitness was quoted as saying some of the larger vessels were “… twinkling like floating hotels.”

![]() Compiled from Charles Bean’s, History of World War One, Volume 9, by Geoff Barker, Collections and Research Services Coordinator, Parramatta Council Heritage Centre, 2014

Compiled from Charles Bean’s, History of World War One, Volume 9, by Geoff Barker, Collections and Research Services Coordinator, Parramatta Council Heritage Centre, 2014

1 The Governor-General, apparently in accordance with a request from the Colonial Office, had telegraphed privately his personal view. This, he believed, would determine the British Government to stop the transports from sailing from Australia but he knew the response would not be in time to stop New Zealand transports due to leave on the 24 September. This was the reason he decided to send New Zealand the message, A Jose, The Royal Australian Navy 1914 -1918, 1933

2 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andrew_Fisher#Third_government_1914.E2.80.9315

3 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cruiser#World_War_I

4 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ronald_Munro_Ferguson,_1st_Viscount_Novar

5 Jose makes it clear that during these events ‘local feeling’, at least as Australia was concerned actually merely the attitudes of Government circles as censorship concerning naval movements was absolute, and the vast majority Australians had no notion of the existence of these problems, or of when the transports were to sail or to what ports or with what escort. A Jose, The Royal Australian Navy 1914 -1918, 1933